Source: The Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare

Recently, India celebrated the World Soil Day with a pledge of the Prime Minister and an app launch by Radha Mohan Singh, the Union Agriculture Minister but a sheer lack of the state capacity is very apparent.

On the occasion of World Soil Day on 5th December, the Union Agriculture Minister stated that 100 million Soil Health Cards distributed to farmers in the first phase (2015-2017). He launched Soil Health Card (SHC) Mobile App. As the minister claimed, the app will benefit field-level workers as it will automatically capture GIS coordinates while registering sample details at the time of sample collection in the field and indicate the location from where the sample has been collected.

Prime Minister of India’s Pledge on the World Soil Day

Soils in India are generally deficient in nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium as several authentic studies showed. It’s noted that such soils do not give high yields. In 2015, the Union Government rolled out a scheme to improve the soil’s health at the national level. Under the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, the

Green Revolution in India escalated usage fertiliser. It is adequately documented that Green Revolution helped in ensuring self-sufficiency in food grains like wheat. But, it encouraged a huge number of farmers to use fertiliser indiscriminately. The official ignorance aggravated the problem. In the couple of decades, a huge number of farmers stopped using the manures which was a traditional way to grow the crops in India.

Soil Health Card (SHM) scheme aims at promoting Integrated Nutrient Management (INM) through judicious use of chemical fertilisers including secondary and micro nutrients in conjunction with organic manures and bio-fertilisers for improving soil health and its productivity.

Shedding light on the scheme, Radha Mohan Singh, the Union Agriculture Minister said, “The key features of Soil Health Card include a uniform approach to collect samples and test them in the laboratory, covering all the land in the country and renew SHC every two years. This scheme is being implemented in collaboration with State Governments. GPS based soil sample collection has been made compulsory to monitor the changes in soil and to prepare a systematic database to compare them with the past years”.

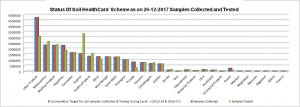

The following graph shows the status of SHC scheme at the national level:

Launching an app for rural India is not enough. Without strengthening the state capacity at the ground level, such schemes are not going to be very beneficial for farmers especially marginal farmers. While writing on this initiative, Harish Damodaran wrote in Indian Express, “A soil testing laboratory can analyse 10,000-odd samples on an average annually. If one-third of 141 million fields are to be covered every year, we would need 4,700 laboratories, as against only about 1,250 —1,050 stationary and 200 mobile – today. How this capacity gap is going to be bridged isn’t clear.” In various districts, there is a sheer lack of a mechanism to deal with these issues. It is very apparent. Such gaps are yet to be fulfilled if the government is really intends to improve the soil condition in India in the backdrop of indiscriminate and lopsided usage of fertilisers for maximising the produce. (Healthy Soil, Wealthy Farmer: Myth or Reality? Earlier, Impact News reviewed this scheme in the backdrop of Three Years of the Modi Government)

It is widely accepted that the sustainable agriculture is an important tool to cope with the pressing problems in the rural India like poverty. Boosting the productivity, profitability and sustainability in agriculture is essential for fighting hunger and poverty.