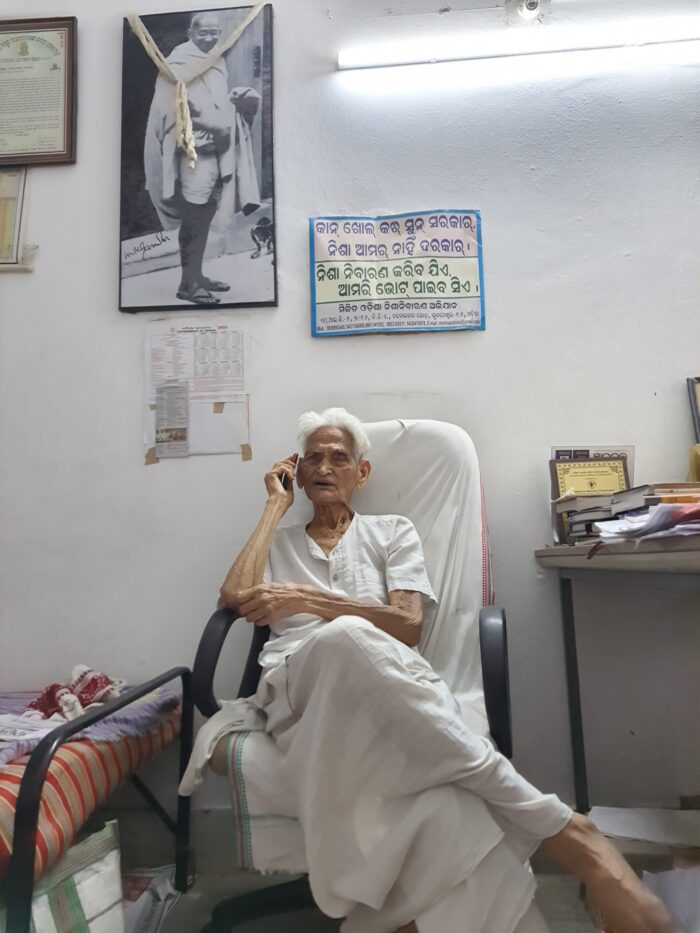

Rasananada Lenka (Picture : Debi Mohanty)

A long seventy five years have gone by. Much has changed in India since the nation attained freedom from the British yoke on August 15, 1947. This Independence Day as India celebrated the Azadi Ka Amrit Mahostav, two individuals, Rasananda Lenka, 91 and Padmacharan Nayak, 97, who had excitedly waited for the historic moment from the afternoon of August 14, 1947 and celebrated the whole night turned nostalgic.

The nonagenarians cherish each glorious moment of that epoch making night. It’s was monsoon season at its peak and the smell of Independence filled the misty air.

Just weeks after spending the summer vacation at home post his eighth class examination, Lenka had entered the night grade at the MKC high school, Baripada- in today’s Mayurbhanj district. Then it’s Mayurbhanj state and was ruled by a benevolent king. “As the King took a lot of care of his subjects, they never felt the oppression of the British rule,” senior advocate at Rairangpur in Odisha’s Mayurbhanj district recalls.

On the afternoon of 14 August, Lenka who had earlier heard about ‘a proposed big celebration’, hurried to the venue: the flourishing market of the Baripada town. By the time he arrived a huge crowd had already swelled. Many more kept trickling in till the late evening.

They talked animatedly, had lot of fun, exchanged greetings and all this went on till the midnight. Came the voice of Pt. Jawaharlal Nehru on the radio. It was pin drop silence, with all eyes fixed on the two transistor sets and ears focused carefully to every single word of the ‘historic, short speech’ by Panditji, India’s first prime minister.

“There were only two transistors in the town, both owned by shop owners in the market. Perhaps some very powerful officials had a transistor at their respective places,” Lenka, 91, recalls. “Those days, radio transmission was done from the centre in Calcutta (now Kolkata). Pt. Nehru’s speech was relayed from Delhi centre and reached us through Calcutta centre,” he adds.

What followed is still etched in Lenka’s memory. Jubilant, they all danced in gay abandon the entire night, sweets were distributed and the dark, cloudy sky was lit up with firecrackers. “That night will live with me always,” puts Lenka.

Nayak, who resides in Bhubaneswar, can’t forget the happenings of that ‘day and night’, either. Then a BSc student at the Revenshaw College Cuttack, Nayak and thousands of his fellow friends assembled at the lush green ground facing their hostels. Like Nayak, many in the gathering had left school during the Quit India Movement of 1942. They nurtured the dream of an Independent India.

The imposing Revenshaw college building was decked up with lights. They were engrossed in debates, shared their thoughts about the country of their imagination. “We were experiencing live our dream shaping into a reality. Naturally, everyone was thrilled,” reminisces, Nayak.

They couldn’t realize when the day had faded into the oblivion and evening had set in amidst chanting: Mahatma Gandhi Ki Jay, Bharat Mata Ki Jay. “Throughout, all of us roared at the top of our voice, and returned to hostels early in the morning of August 15. It’s an amazing feeling,” Nayak tells. It’s not difficult to spot the excitement writ large on his face and also in his voice. For over 14 years, Nayak who was born in 1926 in a village in Kendrapada district-then Kendrapada was under the Raja of Kanika estate-has been spearheading anti liquor movements.

Having nourished political ambitions, Nayak filed nomination from Rajnagar seat in the 1952 elections, but it was cancelled as he fell four days short of the required age to contest MLA election.

Padmacharan Nayak

( Picture : Debi Mohanty

Though in his adolescent years and early youth, he was an ardent admirer of Gandhiji, subsequently Nayak joined the Communist Party, contested assembly elections in 1957. His election expense was Rs 1200. But, he lost.

However, he quit the Communist party and tried his chances again as an independent candidate from the same Rajnagar seat (under Kendrapara Lok Sabha constituency). He won and became a MLA in the Odisha Assembly in 1961. This time, his expenses were a few hundred more though-Rs.1550. “I managed to win by a healthy margin because the entire youths of the constituency were with me,” he concedes.

Around the same time, Lenka, who after his Law degree started his career as advocate in 1960 at the Rairangpur court, had been appointed as the state Youth Congress Organising Secretary. Incidentally, for two successive terms starting 1962, he served as a councilor of Rairangpur NAC. India’s President, Droupadi Murmu became a councilor from there in 1997.

The nonagenarians agree that, since Independence, the country has made ‘unimaginable’ progress. “It’s like hell and heaven, if you compare between then and now,” thinks Nayak. However, at the same time, they believe, India could have achieved much more during these seven decades, too.

According to Nayak, the biggest challenge today is to save our democracy. Unfortunately, elections are won by distributing illegal money and liquor. “We never thought this would be the state of affairs, one day,” he regrets.

Reflecting on his experiences of the 1936-37 provincial elections, which he witnessed as a ten year old, Nayak says, despite primitive means of communication-let alone other facilities, even roads hardly existed in villages- people knew about every action of Gandhiji and his calls reached them through word of mouth. He commanded enormous respect and his influence on the society and polity was unbelievable.

Those days, voting right was limited to very few people who paid a certain amount of annual tax. In that election, freedom fighter Loknath Mishra contested as the Congress candidate from the Patkura seat (now under Kendrapara Lok Sabha constituency). Only a few had seen Mishra before. That was not the age of posters or campaigning. What’s worse, Mishra even couldn’t visit the villages due to lack of roads and water everywhere.

Pitted against Mishra was a powerful candidate, Kanika Raja’s son, Sailendra Narayan Bhanja Deo. The Raja’s son had distributed a few ‘Made in Japan’ cycles-each costing Rs 12- among his election agents. Even, at least two multi color photos of him were pasted in almost every village under the constituency.

Interestingly, to woo the potential voters, boat loads of fish from the Raja’s large ponds were ferried to different places and feasts arranged. Anyone and everyone’s invited. However, the majority didn’t attend. “The people chose not to go there,” recalls Nayak. Polling was held in the police station. Voters put their votes into the two large iron boxes- the one meant for the Congress was yellow in color and the other, red.

When the results were announced, everyone was stunned as Mishra won by a huge margin. “It was entirely due to Ghandhiji’s influence,” says Nayak.

However, he believes, influencing, particularly young voters, began for the first time in 1957. Youth clubs were provided footballs or some other playing equipment, but, nothing more. Money started playing a big role in polls from the eighties. Subsequently, it turned from bad to worse as, along with money, muscle power and liquor made their entry and played a decisive role in elections, he says.

“The saddest part is that the people who are the kings in democracy have been made like beggars in elections these days,” Nayak complains. “We must ban liquor, it has devastated families, corrupted democracy and impacted the nation’s economy and growth,” he argues.

Lenka, though, advocates for the last mile delivery of government’s schemes and policies. “All must know about the schemes meant for them and should have easy access to administration,” thinks Lenka.

He has another demand too: it must be made mandatory for educational institutions to introduce uniforms for students made of Khadi, which would help millions of families working in the Khadi industry.

“The students must be told the idea behind it,” he says, adding, “It would be a tribute to Gandhiji,” Lenka believes.

[the_ad id=”41101″]