7

Brave New Diplomacy in an Uncertain World

A pro-active foreign policy in search of a rightful place in the comity of nations

India, quite surprisingly, began its democratic journey with an insipid mix of offensive and pliable diplomacy. Jawaharlal Nehru would be at his offending best while dealing with the West, especially Americans. His socialist education at Harrow and Trinity would make him loathe the Americans as predatory capitalists with a deficiency in culture. Dean Acheson, the US secretary of state between 1949 and 1953, in his memoir, Present at the Creation, found Nehru ‘prickly’.

He found Nehru ‘one of the most difficult men whom I had ever to deal’.

Here, it needs to be emphasized that the American administration was largely favourable towards India till the late 1960s when the US took an absolute anti-India, pro- China turn under the Nixon–Kissinger supervision. There was a sense of the two democracies coming together sooner rather than later. But India, fresh from its bitter colonial experience, and its national leadership, largely tilted towards the Left, looked at the US with distrust. Even John F. Kennedy, whose inclination in favour of India was obvious and whose admiration for Nehru was unqualified, found the Indian response and reciprocation inadequate, if not scornful.

In JFK’s Forgotten Crisis, Bruce Riedel writes about Nehru’s visit during Kennedy’s presidency in 1961.

One day, the Kennedys, Nehrus and Galbraith sailed on the yacht to Newport. After disembarking, Kennedy drove with Nehru past the enormous mansions of the city’s gilded age and remarked, ‘I wanted you to see how the average American lives,’ to which Nehru cleverly replied,‘Yes, I have heard of your affluent society’ (the title of Galbraith’s most famous book).

[…] During this visit, Nehru was usually taciturn, probably because of his fatigue and jet lag. The President tried to engage him in conversation, but Nehru responded in monosyllables or said nothing at all. As Galbraith wrote in his diary, ‘The President found it very discouraging.’ [American writer and presidential adviser] Ted Sorenson concluded that although the President liked Nehru, ‘that meeting convinced him that Nehru would never be a strong reed on which to rely’. In the end, Kennedy told Galbraith that ‘it was the worst state visit’ of his presidency.7

In contrast, Nehru’s approach vis-à-vis the erstwhile Soviet Union was reverential, if not submissive. When Stalin repeatedly refused to grant an audience to his sister, Vijayalakshmi Pandit8, then India’s ambassador to the USSR, Nehru exhorted her not to lose her cool and maintain composure. It was understandable given how Nehru adored and admired the Soviet Union, especially its economic system.

With the Chinese, too, he was equally deferential. He would, however, at times sound patronizing, which annoyed the Chinese to no end, especially the megalomaniac Mao. Nehru’s India refused a UN Security Council seat, saying China deserved it first—historians may differ on the seriousness of the US and the USSR in offering the seat to Delhi, but there cannot be any disagreement on Nehru being absolutely certain, as his letter to Vijayalakshmi Pandit suggests, about refusing the offer in China’s favour—but such magnanimity would only make Mao more determined to put Delhi in its place. Which it did in 1962. The defeat was an apogee of fifteen years of Nehruvian shortsightedness and blunder.

India, in those days, pursued what veteran journalist and strategic expert Madhav Das Nalapat calls‘cosmic’ diplomacy, which was far adrift from ‘practical, achievable goals that would have better served the interests of the Indian people’. Nalapat explains this in 75 Years of Indian Foreign Policy, ‘When policy reflects less of “what is” and more of “what should be”, such actions may end up doing very little to further actual national interest.’ Maybe Nehru was lucky to have had that long a run. For, when one retains a defence minister, despite knowing his shortcomings, just because he was ‘the only genuine foil Nehru had in the government’ with whom he could discuss Marx and Mill, Dickens and Dostoevsky, as was the case with V.K. Krishna Menon, then it was only a matter of time that India and its political leadership came face to face with the harsh realities.

Menon was a classic exhibition of all that was wrong with Nehruism of the 1950s and 1960s. So pervasive was his anti-Americanism that, as the story goes, he went ballistic when the then army chief, K.S.Thimayya, wanted his troops to be better armed amidst rising threats from China and Pakistan. Thimayya was concerned about the antiquity of the arms his troops were using. But when he suggested to the defence minister the need to replace the .303 Enfield rifle, which had first been used in World War I, with the Belgian FN4 automatic rifle, Menon retorted angrily, come what may, he was ‘not going to have NATO arms in the country!’

Jaishankar begins The India Way, his 2020 book examining India’s ‘strategies for an uncertain world’, with a Satyajit Ray film Shatranj Ke Khiladi depicting the ‘Indian self-absorption’ amid chaos and turmoil. He writes, ‘It [the film] depicted two Indian nawabs engrossed in a chess game while the British East India Company steadily took over their wealthy kingdom of Awadh.’

If the top Indian leadership in the ensuing decade-and- a-half after 1947 behaved like an idealist and ideologue, it exhibited, for almost a decade leading to Independence, the traits of two nawabs engrossed in a game of chess not bothering how the world was changing and, worse, what the enemy was thinking or doing.The timing of the 1942 Quit India Movement is a case in point. Today, a section of intelligentsia accuses Savarkar of being ‘unpatriotic’ for not supporting the 1942 movement. But wasn’t Savarkar sagacious enough to foresee the fallacy of the Quit India Movement?

Book Excerpt : Pg 96-99

A well-researched book that offers a comprehensive analysis of India’s transformative journey from its imperfect start in 1947 to its current status as the fifth-largest global economy.

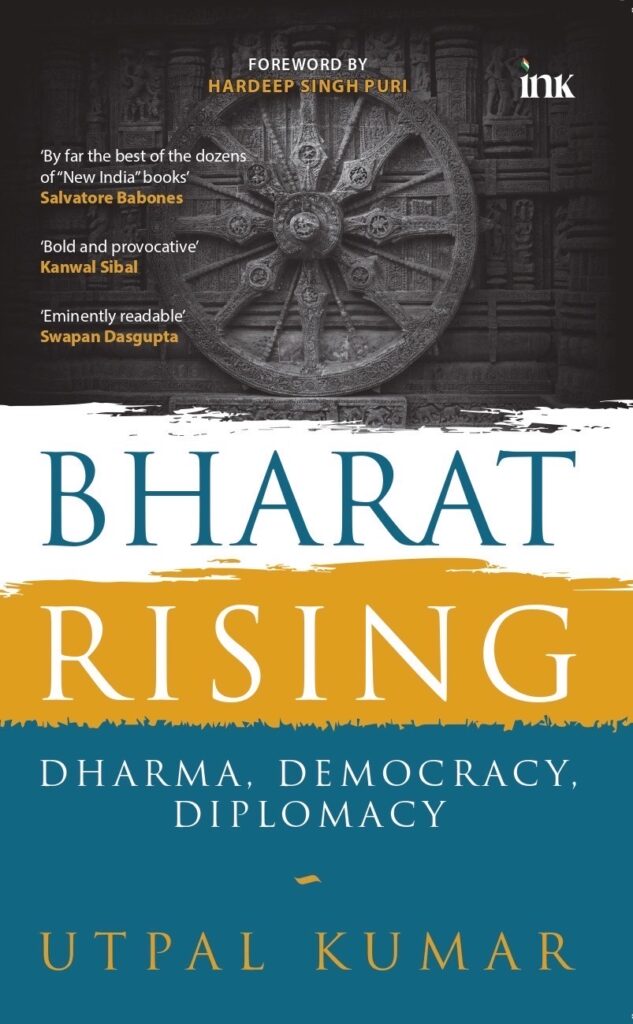

Bharat Rising: Dharma, Democracy, Diplomacy (Ink) by Utpal Kumar not only sets the narrative right about Naya Bharat but also calls the democratic, secular, and liberal bluff of the Nehruvian golden era of the 1950s and after.

(Extracted with permission from the author and the publisher Ink)

[the_ad id=”55724″]