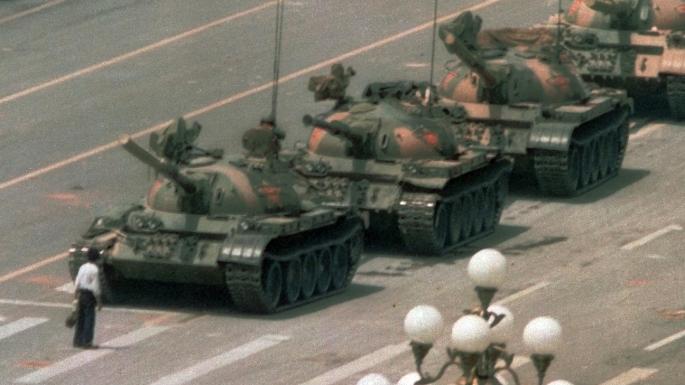

File Picture Courtesy : The Times

China marked 30 years since the deadly Tiananmen crackdown with a wall of silence and extra security after arresting activists and tightening internet censorship ahead of the politically sensitive anniversary.

It was in spring 1989, students and workers gathered at Tiananmen Square — the symbolic heart of Chinese power — demanding democratic change and an end to corruption, inspiring protests across the country.

After seven weeks of demonstrations, the government deployed tanks and soldiers who chased and killed demonstrators and onlookers in the streets leading to the square on June 4.

On a grey, overcast day, police checked the identification cards of every tourist and commuter leaving the subway near Tiananmen Square, the site of the pro-democracy protests that were brutally extinguished by tanks and soldiers on June 4, 1989.

Foreign journalists were not allowed onto the square at all or warned by police not to take pictures.

The United States marked the occasion by hailing the “heroic” movement of 1989 and denouncing a “new wave of abuses” in China.

But in China the Communist Party made sure that the anniversary remained in the distant past, detaining several activists in the run-up to June 4 while popular livestreaming sites conspicuously shut down for “technical” maintenance.

Over the years, the party has censored any discussion of the protests and crackdown, which left hundreds, possibly more than 1,000, dead — ensuring that people either never learn about what happened or fear detention if they dare discuss it openly.

The party and its high-tech police apparatus have tightened control over civil society since President Xi Jinping took office in 2012, rounding up activists, rights lawyers and even Marxist students who sympathised with labour movements.

Countless surveillance cameras are perched on lampposts in and around Tiananmen Square.

“It’s not that we don’t care. We know what happened,” said a driver for the DiDi ride-hailing service who was born in 1989.

“But how can I tell you, the DiDi app is recording our conversation in the car,” he said.

“But today’s China has changed. If you have money you have everything. Without money you dare not open your mouth.” It was largely business as usual at Tiananmen on Tuesday: Hundreds of people, including children waving small Chinese flags while sitting on their parents’ shoulders, lined up at the security checkpoint before dawn to watch the daily flag-raising at the square.

But the line moved slowly due to extra security — with IDs matched on facial recognition screens — and dozens were unable to watch the event.

When asked whether it crossed her mind that she was visiting the square on the 30th anniversary, a nursing school graduate in her 20s from eastern Shandong province said, “What do you mean? No, it didn’t cross my mind.”

Her mother jumped in to say, “We don’t think of that past.”

But there were rare public acknowledgements of June 4 this year.

China’s defence minister, General Wei Fenghe, on Sunday defended the crackdown as the “correct” policy to end “political turbulence” at the time.

The nationalistic state-run tabloid Global Times hailed the government’s handling of Tiananmen as a “vaccination” for Chinese society that “will greatly increase China’s immunity against any major political turmoil in the future”.

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo sharply disagreed on how China has evolved as he hailed the “heroic protest movement” in a statement for the anniversary.

“Over the decades that followed, the United States hoped that China’s integration into the international system would lead to a more open, tolerant society. Those hopes have been dashed,” Pompeo said amid a tense US-China showdown on trade.

Pompeo denounced the “new wave of abuses” by China, including the mass incarceration of Uighur Muslims in the far-west Xinjiang region, and urged a full account of what happened 30 years ago.