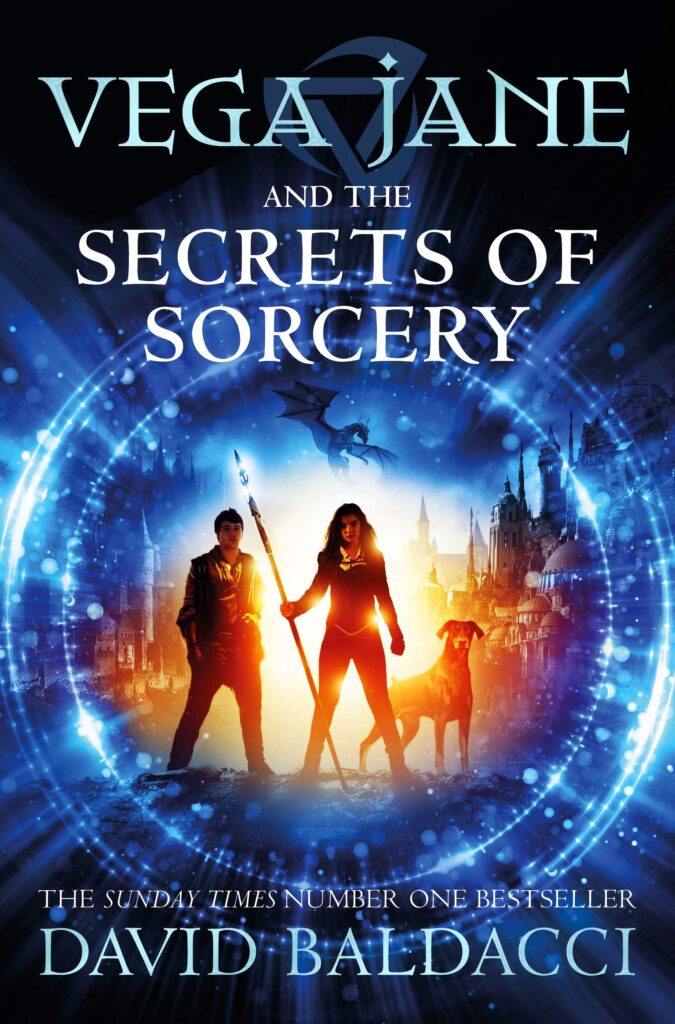

CHAPTER 2 : DELPH

‘Wo-wo-wotcha, Ve-Ve-Vega Jane?’ The voice from below belonged to my friend Delph. His full name was Daniel Delphia, but to me he was simply Delph. He always called me Vega Jane, as though both names were my given one. Everyone else called me Vega – when they bothered to call me anything at all. I said, ‘I’m up here, Delph.’ I heard him clambering up the short boards. Then Delph’s head poked over the planks. He was much taller than me, and I was tall for my fourteen sessions, over five feet, nine inches. I was still growing, because all the Janes were late bloomers. My grandfather Virgil, it was said, grew four more inches when he was twenty.

Delph’s shoulders spread broad, like the leafy cap of my poplar. He was about a session older than me, with a head of thick, black hair that appeared mostly grey-white because of the dust collected there. He worked at the Mill, lifting huge sacks of flour, so he was dusty all the time. He had a wide, shallow forehead, full lips, and eyes that were as dark as his hair. He did not qualify to work at Stacks, where some creativity is required. I have never seen Delph create anything except confusion. No one knew what had happened to him, but something was not quite right with Delph. It had been so ever since he was six sessions old. And yet sometimes he said things that made me believe there was far more going on in his head than most Wugs gave him credit for. I think it would be fascinating to see what went on in Delph’s mind.

He settled next to me, his legs dangling over the edge of the splintered boards. Delph liked to visit me. He didn’t have many other places to go. I pushed my long, dark straggly hair out of my eyes and focused on a dirt spot on my thin arm. I didn’t rub it away because I had lots of dirt spots. And like Delph’s mill dust, what would be the point? ‘Delph, did you hear all that?’ ‘H-hear wh-what?’ ‘The attack canines and the screaming?’ He looked at me like I was mad. ‘Y-you O-OK, Ve- Vega Jane?’

‘The Council was out with attack canines, chasing something.’ I wanted to say chasing someone, but I decided to keep that to myself. ‘They were down near the Quag.’ He shivered at the name, as I knew he would. ‘Qu-Qu-Qu—’ He took a shuddering breath and said simply, ‘Bad.’ I decided to change the subject. ‘Have you eaten?’ I asked. Hunger was like a painful, festering wound for many in Wormwood, including Delph and me. When you felt it, you could think of nothing else. Delph shook his head.

I pulled out a small tin box, which constituted my portable larder. Inside was a wedge of goat’s cheese and two boiled eggs, a chunk of fried bread and some salt and pepper I kept in small pewter thumbs of my own making. Pepper cured many ills, like the taste of bad meat and spoilt vegetables. There had also been a sweet pickle, but I’d eaten it already. I handed him the box. It was intended for my first meal, but I was not as big as Delph. He needed lots of wood in his fire, as they said around here. I would eat at some point. I was good at pacing myself. Delph did not pace. Delph just did. I considered it one of his most endearing qualities.

He wolfed it all down in two swallows. ‘Better?’ I asked. ‘B-better,’ he mumbled contentedly. ‘Thanks, Ve-Vega Jane.’ I rubbed sleep from my eyes. I had been told that my eyes were the colour of the sky. But at other times, when the clouds covered the heavens, they could look quite silver, as though they were absorbing the colours from above. ‘Go-going t-t-to see your mum and dad l-later?’ asked Delph. ‘Yes.’ ‘Ca-can I c-come t-too?’

‘Of course, Delph. We can meet you there after I pick up John from Learning.’ He nodded, mumbled the word Mill, rose and scrambled back down to the ground. I followed him, heading on to Stacks, where I worked to help make hand-crafted items. Now, I didn’t know much. But in Wormwood, I did know that it was a good idea to keep moving. And so I did.

But I did so with the image of someone running into the Quag, when that was impossible because it meant death. And so I convinced myself that I had not seen what I thought I had. Yet not many slivers of time would pass before I realized that my eyesight had been perfect. And that my life in Wormwood would never be the same again.

(Excerpt published with permission from Pan Macmillan India)