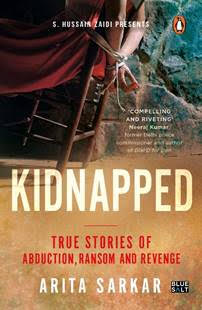

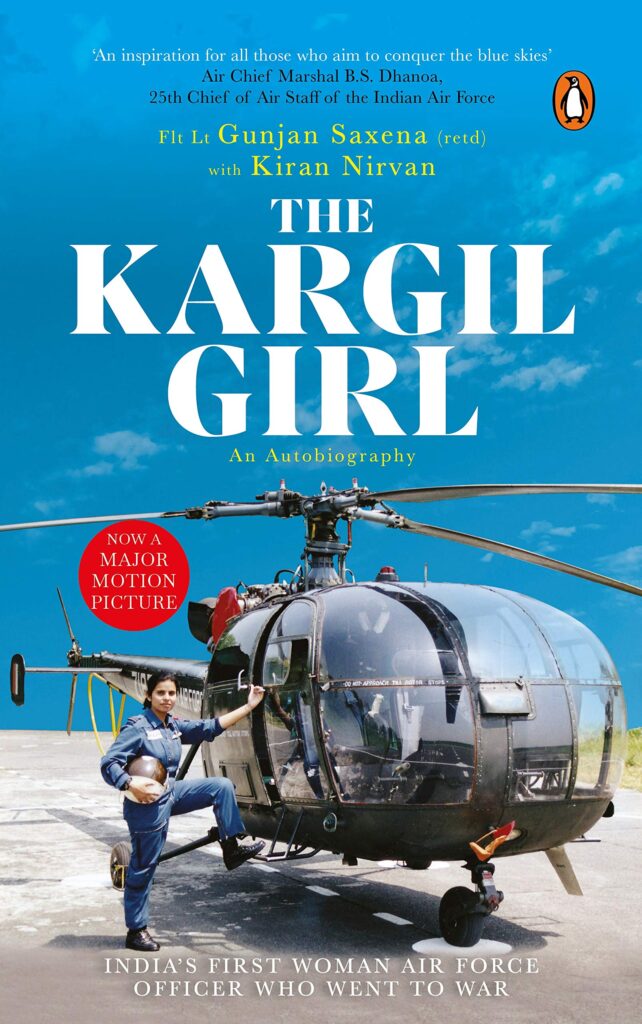

India’s first woman air force officer who went to war and this is her inspiring story in her words.

Chapter : 15

21 June 1999

Pakistan had faced enough humiliation and was on the verge of losing the war, but was still adamant about not

withdrawing its troops from Kargil, even when pressurized by the then president of the United States of America,

Bill Clinton. India, on the other hand, had won one hard-earned victory after another while so many martyrs

registered their respectful names in the history of the nation. Heroes emerged on the battlefield every day. In the

making were exemplary stories of valour that would inspire successors for generations to come.

The war in Kargil had taught me a few lessons as well. I had understood the importance of life and what we must make of it before time ran out. I was making the best of my life while in Srinagar, learning lessons of discipline,

determination, improvisation and ethics on the front line. And yet there was so much more waiting for me.

Eight pilots from my unit, including me, had stationed themselves in Srinagar since the war had begun. As the only female officer in the group, our detachment commander, who was also the flight commander, felt responsible for my well-being under his command. He would keep asking me if I needed anything and urged me to not hesitate in telling him if there was anything that made me uncomfortable. Thinking that I might get uncomfortable at times, he would refrain from sending me on sorties to unknown, isolated locations in the combat zone against my will. Little did he know that he could refrain only until I was the only option left for him.

The flight commander, Wing Commander Srivastav, explained the schedule for the next morning as we were about to sit down for dinner in the dining hall of our detachment. There was a planned communication sortie the next morning and the flight commander, along with another pilot, had to ferry a passenger in his helicopter to a helipad in the forward area; I, along with another pilot in the second helicopter, was supposed to accompany him as his back-up. So it was going to be a simple sortie the next day. The third helicopter of our detachment was supposed to stay in Srinagar with the other pilots, in case any contingency mission came up. After the briefing was over, we sat for dinner.

It was in the middle of our meal that an airman came with a message for the flight commander that the chief operations officer (COO) wanted to speak to him urgently. For a while there was silence around the table, with everyone contemplating what emergency it could possibly be. Such messages always brought anxiety in those days. The flight commander came back and informed us that there was a slight change in the schedule for the next morning. But this change wasn’t going to be altogether comforting, especially for me. A sortie had been planned for casualty evacuation from a helipad very close to the LoC in the Uri sector, the flight commander informed us.

‘But it isn’t as simple as it sounds,’ he added.

‘Why, Sir?’ one of our fellow pilots asked.

But only I had an idea what the flight commander was concerned about.

‘It’s the helipad,’ he said as he stirred his daal.

‘Too close to the LoC,’ another pilot said, ‘but we’ve been to helipads close to the LoC. We know the drill.’

‘Have you been to this one?’ the flight commander

asked, still not eating the food on his plate.

‘No, Sir,’ came a swift reply.

‘Has anyone here been to this helipad?’ a worried flight commander asked.

‘I have, Sir,’ I said, a few seconds after nobody answered.

Suddenly, all heads turned towards me.

‘Gunjan, please tell the others about this helipad,’ he instructed.

‘Navigating to this helipad is quite challenging,’ I started. ‘The valley is quite confusing. There are too many turns and you cannot simply follow the bends of the river below you or the features around you to get there.’

Everyone listened to me quietly, even the flight commander. ‘No sortie is permitted to that helipad if the pilot and the co-pilot have not been there before. Even on occasions that either the pilot or the co-pilot has been there, the pilots have got confused. Their helicopters crossed the LoC and had to be directed back.’

‘So I guess Gunjan will have to switch then,’ one of the pilots said. One thing was sure, and all of us knew it, that I would have to switch with the pilot who was scheduled to wait at the Srinagar airbase the next day for any contingency. There was nobody else among the eight of us who had been to this helipad in the Uri sector before. The flight commander’s sortie was an important one, so he couldn’t have gone with me for this casevac (casualty evacuation). The army had just captured Point 5140, the last objective on Tololing peak. And a VIP, who was supposed to visit there, was the flight commander’s passenger. So the next senior pilot, Wing Commander Joshi, was assigned as the captain of the casevac sortie. But the flight commander had still not said anything about my switching. For a moment I felt that he was concerned about sending a female officer to a mission so dangerous. His concern was valid, since he was responsible for my well-being.

‘Do you still remember the valley’s terrain?’ a concerned flight commander asked. ‘I remember, Sir,’ I said, trying to sound confident even when I was worried inside. ‘Don’t worry, Sir, I will not disappoint you.’ ‘All right, so it’s decided. You go get some sleep. You have to take off at first light,’ said the flight commander, and went back to eating his dinner.

I started sweating about this newly assigned responsibility as I walked to my room. There were no GPS devices in those days, so pilots had to familiarize themselves with the map and the actual terrain for navigation. Scenes from the previous sortie to this helipad started flashing in front of my eyes. But more than a year had passed, and it was all too blurry. I had assured the flight commander for two reasons—it was a casevac, so someone’s life was at stake, and it was also an opportunity for me to prove myself.

No sooner had I entered my room than I took out the map of the valley and started going through it carefully. When I had gone to this helipad before, I had gone with a senior pilot who had earlier been there. The responsibility of navigation had not fallen to me then. And there was no war going on back then. If one crossed the LoC now, things could get worse. After all the necessary preparations on the map were done, I went to sleep. I had to wake up fresh the next day. But even after a while, I felt myself struggling to sleep as thoughts about what could go wrong flooded my mind. It was then that I remembered what the captain of my previous sortie to this helipad had taught me— something that would hold me in good stead the next day.

There was a particular turn in this valley where pilots usually got confused. The key to not getting confused was timing. In flying, when a pilot takes off he/she is supposed to bring the aircraft to a particular height and then set the course at a constant speed. This constant speed and distance to the helipad could be used to calculate the time it would take to reach that confusing turn to avoid any trouble. Since the flying distance to that helipad was not much, the time required for this calculation was also very less. But now I knew what I had to do. Soon, I fell asleep.

The next day I woke up even before the alarm went off. I prepared myself for the sortie and went to the helicopter.

This mission had no margin for error. No time for a recce would be available once airborne and the luxury of

hovering over the area to spot the helipad was not there due to its location very close to the LoC.

‘All the best, Gunjan. Do everything right,’ Flight Lieutenant Kagti, who was the only officer there with the same seniority as mine, said to me as he walked past me to the helicopter that I was supposed to fly earlier. He was the one I had switched with.

‘I don’t know, I’m just nervous,’ I said.

‘You weren’t trained to be nervous,’ he said, and smiled before getting into the cockpit. I replied with a bleak smile. But he was right. I wasn’t trained to let nervousness jeopardize a mission. I did not pass out from the academy with flying colours just to get nervous. I was very much capable of pulling it off, I assured myself. With this as a reminder, I got inside the cockpit as soon as the captain arrived.

‘I hope your photographic memory serves you well today. Now let’s get to the start-up procedure,’ the captain said, as he strapped himself to his seat. He noticed that I was a bit shaky in my start-up procedure. He could see that I was still nervous. And there was no denying that I was.

And then we took off. We orbited over Srinagar to gain height up to 5000 feet for vertical clearance from small arms fire or shoulder-fired missiles. During the climb, I mentally shook myself and told myself I couldn’t be jittery about this any more. Pulling myself together, I took out the map, took the bearings, did my calculations for timing based on the ground speed, adjusted our ETA and switched on the stopwatch to ensure I did not overshoot our position.

As per standard operating procedure, if we failed to spot our helipad by the calculated time, we were to return without completing the casevac, because hovering was prohibited in that area due to the dangers involved. And

I did not want to deprive a casualty of a chance at getting proper medical aid. The life of a soldier was at stake, and I did not want to fail. I was responsible for navigating and finding the helipad. Failing to do so, I would be held responsible for the unsuccessful sortie and my experience of flying in this area would go in vain. Not only this, my flight commander’s faith in me would be shaken.

As we entered the valley, I concentrated only on the navigation. After only a few minutes, the stopwatch indicated that the turn had come. But I couldn’t identify it as I looked down at the valley, and it made me nervous. Nevertheless, I was confident that I had calculated the timing right, so I took the turn. ‘I can’t spot the helipad, can you?’ the captain asked. I desperately scanned the area below to see if I could spot it. As per the stopwatch, only thirty seconds were left to reach the destination and if we didn’t spot the helipad, we would have to turn around and go back.

‘There it is!’ I exclaimed joyfully as smoke from the smoke candles became visible. Smoke candles were lit by the army near the helipad to help us spot it. I finally relaxed. My captain relaxed too. A sense of achievement pumped inside me.

Smoke swirled under the powerful rotors of our helicopter and waves of dust swept across the helipad as we descended. As soon as we landed and signalled the team there, stretcher bearers ran towards the helicopter with the casualty. The rotors were kept engaged, since time was of the essence. We took off as soon as the stretcher bearers got to a safe distance away from us. A major-ranked officer in charge of that unit smiled at us and gave us a thumbs up as he stood at the edge of the helipad clad in his worn-out dungarees. I smiled back, and flew away from the valley.

The mission had been a success and I couldn’t wait to see the look on my flight commander’s face. I hadn’t let

him down. I was happy that even with less than three years of service, I had been considered for such a difficult sortie and I had pulled it off.

With India slowly emerging victorious in this war, a sulking Pakistan Army was trying to cause maximum damage to the Indian side, and its ill intentions led to an incident that shook me to such an extent that I was left scared for the first time since the war had begun.

(‘Excerpted’ with permission from Penguin Random House India)

[the_ad id=’22722′]