SECTION ONE – IN THE COMPANY OF GIANTS

CHAPTER 7 – Modi’s Appropriation Of Patel

Narendra Modi made a shrewd domestic political calculation- that wrapping himself in the mantle of other distinguished Gujaratis, notably Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel , would enable some of their lustre to rub off on him.

The process has already begun , lest we forget, when then chief minister Modi moved aggressively to lay claim to the legacy of one of the India’s most respected founding fathers , Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, before the 2014 election. I n his quest to garb himself in a more distinguished lineage than his party can ordinarily lay claim to, Modi called on farmers across India to donate iron from their ploughs to construct a giant, nearly 600- foot statue , of the Iron Man in his state , which be by far the tallest statue in the world , dwarfing the Statue of Liberty. But it will be less of a monument to the modest Gandhian it ostensibly honours than an embodiment of the overweening ambitions of its builder – who decided to get Chinese foundry to cast it, for his ambitions exceeded India’s capabilities.

Modi’s motives are easy to divine . As his own image was tarnished by the communal massacre in Gujarat when he was the chief minister in 2002, identifying himself with Patel { who is portrayed as the leader who stood for the nation’s Hindus during the horrors of Partition and was firm on issues like Kashmir} is an attempt at character building by association – portraying Modi himself as an embodiment of the tough, decisive man of action that Patel was, rather than the destructive bigot his enemies decry.

It helps that Patel is widely admired for his extraordinary role in forging India that gave him an unchallenged standing as the Iron Man. Patel represents both a national appeal and a Gujarati origin that suits Modi. The Modi – as- latter-day- Patel message has been resonating well with many Gujaratis, who are proud to be reminded of a native son the nation looks up to, and with many of India’s urban middle- class, who see in Modi a strong leader to cut through the confusion and indecision of India’s messy democracy.

But Patel’s conduct during the violence that accompanied the Partition stands in stark contrast to Modi’s in 2002. Both Patel and Modi were faced with the serious breakdown of law and order in their respective domains, involving violence and rioting against Muslims. In Delhi in 1947 , Patel immediately and effectively moved to ensure the protection of Muslims, herding 10,000 in the most vulnerable areas to the security of Delhi’s Red fort. Because Patel was afraid that the local security forces might have been affected by the virus of communal passions, he moved army troops from Madras and Pune to Delhi to ensure Law and order. Patel also made it a point to send a reassuring signal to the Muslim community by attending prayers at the famous Nizamuddin Dargah to convey a clear message that Muslims and their faith belonged unquestionably on the soil of India . Patel went went to the border town of Amritsar, where there were attacks on Muslims fleeing to the new Islamic state of Pakistan and pleaded with Hindus and Sikh mobs to stop victimising Muslim refugees . In each of these cases , Patel succeeded and there are literally tens of thousands of people who are alive today because of his intervention .

The contrast with what happened in Gujarat 2002 is painful. Whether or not one ascribes direct blame to Modi for the pogrom that year , he can certainly claim no credit for acting in the way Patel did in Delhi. In Gujarat, there was no direct and immediate action by Modi, as the state’s chief executive, to protect the Muslims. Nor did Modi express any public condemnation of the attacks , let alone undertake any symbolic action of going to a masjid or visiting a Muslim neighbourhood to convey reassurance.

There is a particular irony to a self – proclaimed ‘ Hindu Nationalist ‘ like Modi laying claim to the legacy of a Gandhian leader who would never have qualified his Indian nationalism with a religious label. Sardar Patel believed in equal rights for all irrespective of their religion or caste, it is true that at the time of Partition Patel was inclined to believe , unlike Nehru, that an entire community had seceded. In my biography, Nehru : The Invention of India , I have given some examples of Nehru and Patel clashing on this issue. But there are an equal number of examples where Patel , if he had to choose between what was the right thing for the Hindus and what was right morally , invariably plumped for the moral Gandhian approach.

An example , so often distorted by the Sangh Parivar apologists , was his opposition to Nehru’s pact with Liaquat Ali Khan, the prime minister of Pakistan , on the question of violence in East Pakistan against the Hindu minority. The Nehru – Liaquat Pact was indeed criticized by Patel , and he disagreed quite ferociously with Nehru on the matter. But when Nehru insisted on his position , it was Patel who gave in, and his reasoning was entirely Gandhian : that violence in West Bengal against Muslims essentially took away Indians’ moral right to condemn violence against Hindus in East Pakistan. That was not a Hindu nationalist position but a classically Gandhian approach as Indian nationalist.

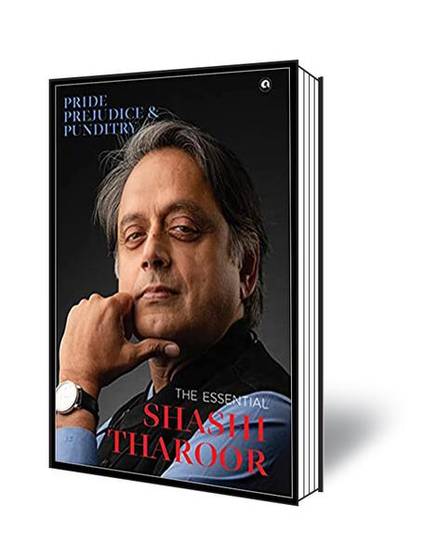

(‘Extracted from Pride, Prejudice, and Punditryby Shashi Tharoor , with permission from Aleph Book Company’)

[the_ad id=”41101″]