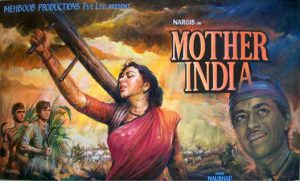

Image: Representative Purpose

By Roshni Sengupta

That the world is in a state of flux is in plain sight, for all to see and comprehend. From the rise of chest-thumping, ultra-nationalist majoritarian forces in India to the venomous import of Trumpspeak in the United States, from the far-right taking over popular support in a majority of the European Union states to conservative politics being at the helm in Japan, causing the most fundamental of freedoms and the most basic rights to be called into question, the shift from a liberal discourse to a fearfully conservative one seems to be clearly in process. In a scenario such as this, the very definitions of all that individuals really took for granted are being altered, in the most damaging ways. Nationalism has – rather precariously – emerged as the holy grail of the debates ensuing in the light of such remarkable transformations in world politics. Much of these deliberations, given the technological advancement of our age, have begun to take place in television studios, fine print, online or, very importantly on celluloid. In the immediate aftermath of the events of September 11, 2001, the aesthetic of politics in American cinema and television changed in a very vital manner. Paranoia, fear and all-pervasive insecurity seemed to have become the benchmarks of cinematic narratives, pushing consistently for popular support for stringent security measures. Popular Hindi cinema – or Bollywood – also responded to the changing political narrative by producing its own version of 9/11 cinema where notions of nationality and citizenship were essential engagements. A very clear political discourse seemed to emerge as an indelible line came to divide the world into ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Such a binary critically amends the very definition of nationalism – presenting immediately a negatively construed corollary of ‘anti-national’. Subsequent events in India have led to similar ideological distinctions used to divide populations – if you are not with the majoritarian forces, you are with ‘them’, the enemy! Sounds ridiculously analogous to George W Bush’s credo, “if you are not with us, you are with the terrorists”. A familiar discourse has hegemonized various media, including cinema. It becomes important to note however that although the present-day popular discourse seems tuned towards majoritarianism, hyper-nationalism and a pernicious form of segregation of populations based on religion or creed, Indian cinema has also been a site for alternative ideological examinations. The years after Independence saw popular Hindi cinema give the call for ‘all hands on deck’ as the nation was firmly on its way towards development and prosperity, while the nascent Indian middle class and its travails became the subject of cinematic pursuits soon after, with the subsequent years reflecting the death of the Nehruvian dream and the angst of the common Indian faced with a downward spiral. The meteoric rise of Amitabh Bachchan as the ‘angry young man’ – the embodiment of the failure of the Indian state to realise the potential that presented itself at Independence – defines the shifting ideology of Bollywood. Cinematic reactions to the volatility of Indian politics and society became the stuff of legend with narratives like Sholay(1975), Zanjeer (1973), Deewar (1975), Trishul (1978), Andha Kanoon (1983), Laawaris (1981), Agneepath (1990), and Shehenshah (1988) arguing for a just society while locating fictional characters in real-life milieus replete with debilitating economic and social inequalities, systemic corruption, and a general sense of gloom. These Amitabh-starrers not only were representative of the hopelessness that pervaded social articulations but were – in affect – driving the requiem for betterment through the persona of the ‘hero’. The ‘nation’ – in all its microcosmic splendour – came to be summarily defined as unequal and unjust, fuelling the spirit of rebellion among the youth which ultimately came to fruition with the elimination of those responsible for the situation and the establishment of a just order. Nationalism, in popular cinematic discourse during this period, remained an ideological quest, with social ills impeding the process every step of the way.

A genre of Bollywood cinema that merits engagement in the context of nationalism in cinema are ‘war films’ or narratives that represent conflict – past and present. The Bollywood ‘war’ film makes for compelling viewing – it has historically produced some of the most scintillating camera effects. Aside from the technical magnificence of war cinema, the discursive tropes of these narratives almost always have not only resurrected but also constructed the ‘enemy’ – ‘them’. If in Haqeeqat (1964), the ‘them’ were the Chinese, in one war narrative after another, the enemy is Pakistan! Border (1997), LoC-Kargil (2003), Lakshya(2004), and Ab Tumhare Hawale Watan Saathiyon (2004) have not only cinematically recreated events during the 1971 war with Pakistan and the Kargil conflict, but have successfully renegotiated terms of reference while representing the enemy – Muslim, Pakistani, terrorist! Along with the adrenaline rush that war narratives provide to a fawning audience, they symbolise an extremely malevolent imagination of the enemies of the ‘nation’. Narratives like Border, with their over-the-top jingoism, somehow become benchmarks of victory in war, vanquishing the enemy…nationalism. The loud, vitriolic nationalism of Gadar (2001) or Zameen (2003) has made its way – it does appear – into popular discourse, especially in present times, translating into easy categories into which ‘anti-nationals’ are placed – baseless and fluid – such as pro-Pakistani, anti-Hindu, Communist! Homogenization of the most malicious kind has been normalized, setting off a dangerous trend for the future.

This special issue of Café Dissensus acknowledges and engages with a number of issues around the broad theme ‘Bollywood Nationalism’ in the form of sixteen thoughtful and perceptive essays. Even though I personally detest the idea of categorising – thoughts or people – the essays have been divided into sections for the sake of discursive convenience. Needless to say, each of these insightful pieces could be read as articulations of great depth and discernment. I hope the readers of Café Dissensus would enjoy reading this issue of the magazine. Of course, your thoughts and comments are most welcome!

Bio: Roshni Sengupta is a lecturer at Leiden Institute for Area Studies, Leiden University and can be reached at rosh.sengupta@gmail.com.

(The article first appeared on Café Dissensus. To read the original article click Here.)